4.8 KiB

4.8 KiB

marp, paginate, theme, footer, style

| marp | paginate | theme | footer | style |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| true | true | rose-pine | EidP 2024 - Nils Pukropp - https://git.narl.io/nvrl/eidp-2024 | .columns { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(2, minmax(0, 1fr)); gap: 1rem; } |

Tutorium 14 - 2025-01-23

Closures, Automaten, Decorator, Blatt 13

Closures - Wiederholung

Closures sind Funktionen, bei denen Variabeln den aktuellen Scope, also die Umgebung der Funktion verlassen

Beispiel:

def make_dividable_by(m: int) -> Callable[[int], bool]:

def dividable(n: int) -> bool:

return n % m == 0

return dividable

Automaten - Was ist das?

- Mit Automaten werden endlich deterministische Automaten gemeint

- Müssen endlich sein

- Müssen deterministisch sein

- Nennt man DEA

DEA - Etwas formeller definiert

DEA sind 5-Tupel, also \mathfrak{A} = (Q, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, F), wobei

Qdie endliche Zustandsmenge ist\Sigmadie Eingabe-Menge ist\delta : Q \times \Sigma \rightarrow Qdie Übergangsfunktionq_0 \in Qder StartzustandF \subseteq Qdie Menge der Akzeptierenden Zustände

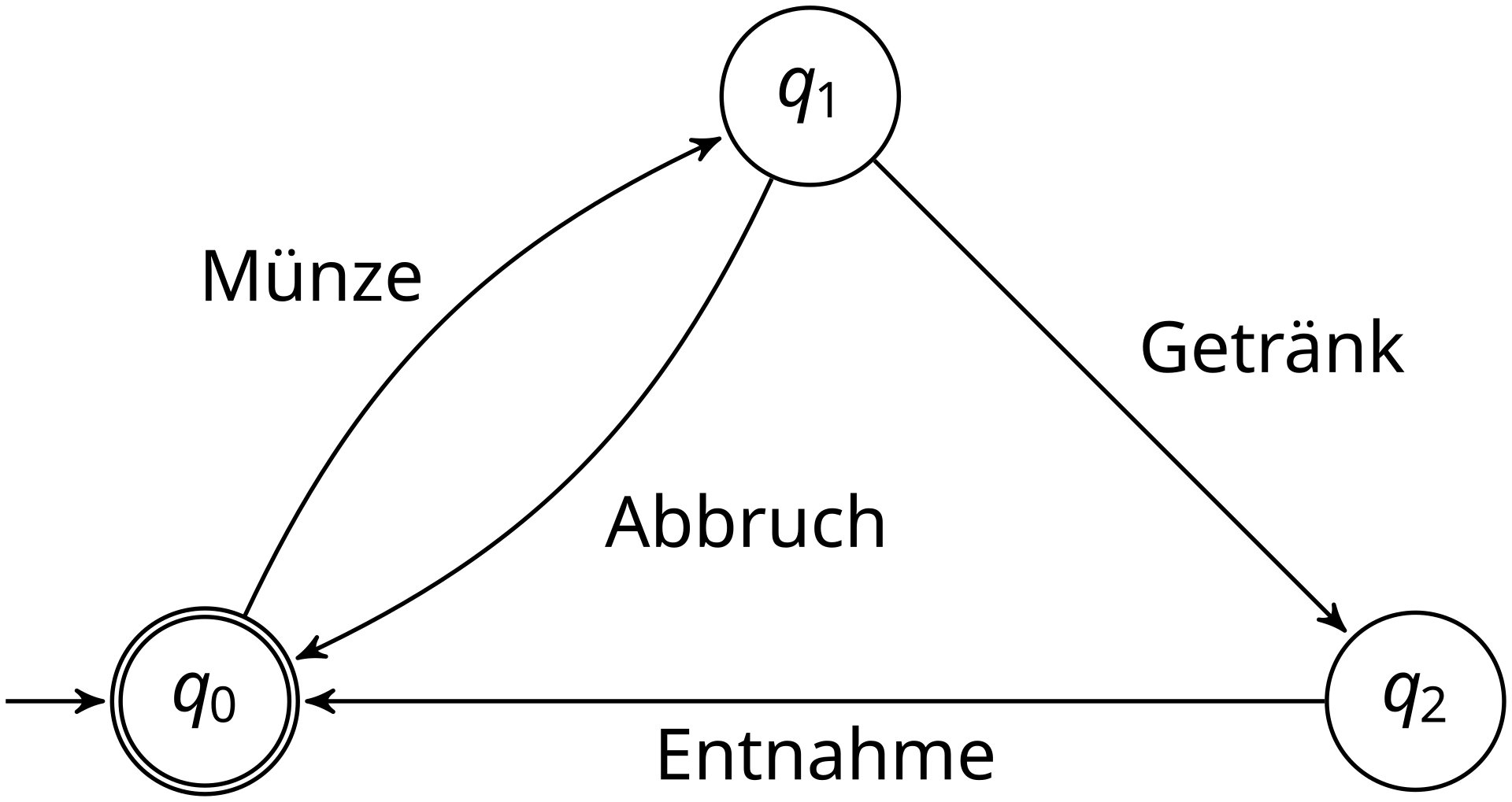

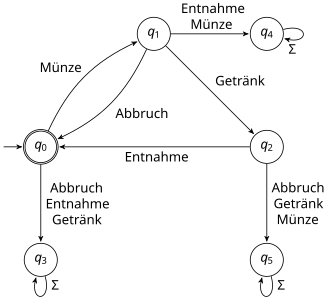

formelles Beispiel

Q := \{q_0, q_1, q_2\}\Sigma := \{\text{Münze}, \text{Abbruch}, \text{Getränk}, \text{Entnahme}\}\delta : Q \times \Sigma \rightarrow Q(q_0, \text{Münze}) \mapsto q_1(q_1, \text{Abbruch}) \mapsto q_0(q_1, \text{Getränk}) \mapsto q_2(q_2, \text{Entnahme}) \mapsto q_0

q_0StartzustandF := \{q_0\}

Genau genommen ist der Beispiel-Automat nicht deterministisch, warum?

DEA in Python

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Automaton[Q, S]:

delta: Callable[[Q, S], Q]

start: Q

finals: frozenset[Q]

def accept(self, input: Iterable[S]) -> bool:

state = self.start

for c in input:

state = self.delta(state, c)

return state in self.finals

Decorator

- Design-Pattern, oft auch Wrapper genannt

- Verpackt ein Objekt um zusätzliche Funktionalität zu bieten

- Funktionen sind auch Objekte

- eine Klasse ist ein Objekt

- Oft einfach syntax sugar

Beispiel - execute_two_times

def execute_two_times(fn: Callable[..., Any]) -> Callable[..., Any]:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs)

fn(*args, **kwargs)

fn(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

return wrapper

@execute_two_times()

def print_two_times(msg: str):

print(msg)

print_two_times("hello") # hello

# hello

Beispiel - execute_by

def execute_by(n: int):

def wrapper(fn):

def wrapped_fn(*args, **kwargs):

for _ in range(0, n):

fn(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapped_fn

return wrapped_fn

return wrapper

@execute_by(10)

def print_ten_times(msg: str):

print(msg)

print_ten_times("hello") # hello

# hello

# ... (10 mal)

Beispiel - CommandDispatcher

class CommandDispatcher[R]:

def __init__(self):

self.__commands: dict[str, Callable[..., R]] = {}

Beispiel - run

def run(self, name: str, *args, **kwargs) -> list[R]:

results : list[R] = []

for command_name, command in self.__commands.items():

if command_name == name:

results += [command(*args, **kwargs)]

return results

Beispiel - register

def register(self, cmd: Callable[..., R]) -> Callable[..., R]:

self.__commands[cmd.__name__] = cmd

return cmd

Beispiel - CommandDispatcher

class CommandDispatcher[R]:

def __init__(self):

self.__commands: dict[str, Callable[..., R]] = {}

def run(self, name: str, *args, **kwargs) -> list[R]:

results: list[R] = []

for command_name, command in self.__commands.items():

if command_name == name:

results += [command(*args, **kwargs)]

return results

def register(self, cmd: Callable[..., R]) -> Callable[..., R]:

self.__commands[cmd.__name__] = cmd

return cmd

Beispiel - How to use

app = CommandDispatcher()

@app.register

def hello_world() -> str:

return 'hello_world'

@app.register

def divide(a: int, b: int) -> str:

if b == 0:

return "tried to divide by zero"

return str(a / b)

print(app.run('hello_world'))

print(app.run('divide', 5, 0))

print(app.run('divide', 10, 2))

Decorator in der Klausur

- Waren noch nie Bestandteil der Klausur

- Mut zur Lücke

- Kann euch natürlich nichts versprechen